|

Back to Index

Real,

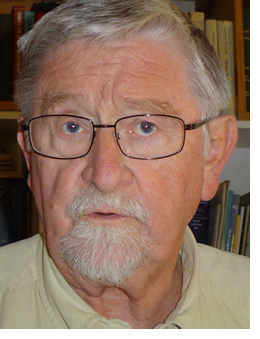

positive values - Interview with Professor Reginald H Austin

Upenyu

Makoni-Muchemwa, Kubatana.net

June 16, 2010

Read

Inside / Out with Reg Austin

Professor

Austin is a Zimbabwean law professor who was active in the liberation

struggle and a member of the legal team at the independence negotiations

at Lancaster House in London in 1979. He worked with the United

Nations in several of their Election Observer Missions and has successfully

organised elections in Afghanistan and the Solomon Islands. Source:

www.sardc.net/board.asp Professor

Austin is a Zimbabwean law professor who was active in the liberation

struggle and a member of the legal team at the independence negotiations

at Lancaster House in London in 1979. He worked with the United

Nations in several of their Election Observer Missions and has successfully

organised elections in Afghanistan and the Solomon Islands. Source:

www.sardc.net/board.asp

More recently

Professor Austin was appointed Chairperson of the Zimbabwe Human

Rights Commission.

You

were part of the legal team at the Lancaster House negotiations,

what were the issues surrounding land then?

I was working with the ZAPU Delegation. Our position was that we

wanted to have an agreement, which would enable radical land reform

to take place. There were various models in mind at that stage;

one for example was the Kenyan Million acre scheme. There were certain

bottom lines that we had in terms of negotiations. For example,

it was suggested that as compensation for land that might be taken,

the level of compensation be similar to that provided in the Protocol

for the European Convention, which is fairly straightforward. But

that was unacceptable to the British. They were absolutely adamant

that there must be severe and extreme protection of white owned

commercial land. So we had section 16 (of the Lancaster House Agreement

forced on us). The land issue was a break issue, and it was only

saved by pressure upon the Liberation Movement from its friends,

the frontline states and promises by the British and the Americans

who indicated that a radical land reform programme could be carried

out, even under the difficult circumstances because the money would

be made available. That was the offer that was made at a stage when

the Liberation Movement was ready to break the conference. What

we were faced with as the Liberation Movement was that for the past

fifteen years, at least, there had been a very significant slogan:

"The Land belongs to the People" and we needed somehow

to come out of the conference with an agreement which showed that

the land did belong to the people. In fact as it happened with a

very different arrangement. That the Land would have to be paid

for in foreign currency and it had to be on a willing buyer willing

seller basis. It was a bitter disappointment without a doubt.

What

are your thoughts on the current issues being debated regarding

land tenure in Zimbabwe?

What we basically had was a revolution within a revolution. The

land aspect of the revolution broke a very basic principle of the

previous system which was land tenure, sale purchase and registration.

Those titles, which historically are the basis of lending money

etc, have been undermined. The only way to get back a situation

where those in possession of the land are able to use it productively

by having money will be for a going back to basics. Finding a new

basis for the ownership of land. It means that at some point there

will need to be a going back to the basic principle of compensation,

which was the principle that we started with. The question is how

do we get the compensation? Part of the solution was that there

would be money made available from those who had taken the land

right up to the 1950s. All that period was a period when legal responsibility

rested with the British Government - they were seen as an essential

part of the solution. We have to get back to a state of stability.

How to get back to that is going to be a very big problem. It-s

going to require some very tough negotiations and solutions.

You

were appointed Head of the Human Rights Commission in March. What

is the Commission-s mandate?

The mandate is set out very briefly in Section 100R of the Amendment

to the Constitution that is basically to create a commission that

will promote and protect human rights; it will have powers of investigation

and cooperate with both the authorities and civil society. Its very

basic, it needs a great deal more detail. That will be provided,

as in other countries by a Human Rights Act, which will set up in

detail the status and mandate of the institution. Until we have

that act we will not know precisely what our mandate is, and the

public will not know precisely what our powers are. It-s a

matter for Parliament to decide what kind of institution we will

be, whether we will work towards national reconciliation, whether

we will become a forward looking institution, particularly when

changing or developing a culture. That will depend also upon the

Constitution that we have. Our Constitution will tell us, and the

other state institutions, what our principles or basic values are.

So the Constitution making process is very important to the Human

Rights Commission and other state institutions.

What

kind of future would you like for Zimbabwe?

I would like a future for Zimbabwe which is based on, what I believe,

are the real positive values that Zimbabwean people have. They-re

very conservative, but based on the ideal respect. That sort of

value system is to be shared not just by the people but also by

the institutions that governs them. That would produce what I have

always thought to be a pretty fantastic country.

Visit the Kubatana.net

fact

sheet

Please credit www.kubatana.net if you make use of material from this website.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License unless stated otherwise.

TOP

|