| |

Back to Index

Pop

goes the easel

Bongani

Madondo, The Sunday Times (SA)

May 01, 2005

http://www.suntimes.co.za/articles/article.aspx?ID=ST6A116839

Read more about

Kudzanai Chiurai's exchibition called 'Y Propaganda' at

http://www.obertcontemporary.com

Zimbabean

artist Kudzi Chiurai is about to explode onto the local scene. Bongani

Madondo talks to a young man taking up arms against history

This work is

licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.

The

omnipresent eye of President Robert Mugabe keeps watch on every

brush stroke and aerosol spray Kudzanai Chiurai puts on his canvasses

- or so he thinks. The artist known by his trademark, Kudzi, is

a deeply troubled man and a brilliant talent. The 24-year-old who

arrived in South Africa five years ago to study fine arts at Pretoria

University, says art is his life. Kudzi is a paint-bespattered fugitive,

ducking and diving the claws of his countryís president ... Is that

it? "No," he says when we meet in his jumbled studio in Braamfontein,

Johannesburg. "I donít necessarily think Iím on Zimbabweís most-wanted

list, but who knows? I canít stop feeling troubled by how my work

might be interpreted." Kudziís larger-than-life, mixed-media works

combine political satire, hard-edged hip-hop graffiti, poetry, architectural

design and commentary on big cities to produce pop art. His is a

political pop deeply embedded in the impressionist tradition - and

not in the advertising industryís variation of pop art. The

omnipresent eye of President Robert Mugabe keeps watch on every

brush stroke and aerosol spray Kudzanai Chiurai puts on his canvasses

- or so he thinks. The artist known by his trademark, Kudzi, is

a deeply troubled man and a brilliant talent. The 24-year-old who

arrived in South Africa five years ago to study fine arts at Pretoria

University, says art is his life. Kudzi is a paint-bespattered fugitive,

ducking and diving the claws of his countryís president ... Is that

it? "No," he says when we meet in his jumbled studio in Braamfontein,

Johannesburg. "I donít necessarily think Iím on Zimbabweís most-wanted

list, but who knows? I canít stop feeling troubled by how my work

might be interpreted." Kudziís larger-than-life, mixed-media works

combine political satire, hard-edged hip-hop graffiti, poetry, architectural

design and commentary on big cities to produce pop art. His is a

political pop deeply embedded in the impressionist tradition - and

not in the advertising industryís variation of pop art.

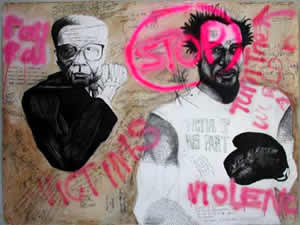

His large-scale

(3.66m x 2.44m) combinations of graffiti, etchings, ink drawing,

poetry and watercolours give a sense of a film in progress - the

only difference being that the images are frozen on the hardboard

on which he chooses to work. In an age where young artists seem

to be absorbed by graffiti, self-righteousness, or film and advertising

jobs - while older artists are commemorated in one retrospective

after another - Kudziís arrival and innovative use of street aesthetics

to illuminate his conceptual art promises to add zing to the local

scene. His brooding, paranoid, funereal and sometimes colourful

mixed-media works have thrust him forward as one of the possible

heirs to the legacy of US artist Jean Michel Basquiat. As a painter,

Kudzi deals with urban African issues with the same subversive and,

at times, mad humour as the Zimbabwean novelist Dambudzo Marechera

(The House of Hunger). His work charms and chokes. Humour is an

integral part of his work and the joke is not on the subjects he

tackles with rib-cracking style, but on us, the viewers.

And while Mugabe

- his hair flaming orange and spiked to suggest the ageing politician

is a devil - seems to pop in and out of Kudziís work with ease,

the Zimbabwean president is not a subject he discusses easily. "My

work narrates a variety of stories, well beyond Mugabe. Uncle Bob

is just one of them. Iím keen on themes such as censorship, fear,

paranoia, popular culture and inner-city movements ... the individualís

place within the jungle that a big city like Johannesburg is. He

[Mugabe] does not define my work, though as a Zimbabwean he is this

omnipresent, heroic, self-centred, funny, brutal, visionary, regressive,

oppressive figure - the embodiment of what is great and messed with

Zimbabwe," says Kudzi. "Whether you are an artist, an accountant,

a man of the cloth or a sports player, in or outside Zimbabwe, Mugabe

is somebody you cannot not deal with. He lives in our lives. It

is quite a stressful undertaking. A yoke many are reluctant to bear.

Some carry it inside themselves, hidden, afraid to speak about it

in public, but privately deranged. I guess I wear mine on my sleeve.

I lay it out for all of us to deal with. It is terribly risky -

that I am aware of - but I have to do it."

"Why?"

I ask. "Iím an artist and besides, it is what I know, what I understand,"

says Kudzi. "So you still believethereís glamour in an artist dying

a heroic death?" "Rather the opposite. I think the artist should

live longer to record atrocities and beauty. But I am not about

to paint flowers, not now anyway. Still, you can neither practise

nor dream if fear is a constant factor in your life. In any case,

life is about that: everything, every action is political. It can

be documented and reviewed according to the viewerís taste." Though

he has created only three works which deal directly with the spectre

of Mugabe - The Presidential Wall Paper, The True Believer and The

End of Silence - the artist often finds discussing Zimbabweís bespectacled

kingpin harrowing. "I might sound brave, but I am very disturbed.

I am concerned about my family. I am torn apart... you see, my mother

still lives in Zimbabwe. I also love the country. I still want to

go back. Itís been three years since I last went back. The country

is in my bloodstream." The third time I meet Kudzi, our talk is

all about the identity he is creating and about living in a country

that is, like its President, torn between pro- and anti-Mugabe camps.

He is acutely aware of the battle lines - between those who passionately

feel that quiet diplomacy is a game for wild birds, and that Mugabe

should be pressured to step down; and those who are motivated by

a different set of racial and economic considerations. "Why?"

I ask. "Iím an artist and besides, it is what I know, what I understand,"

says Kudzi. "So you still believethereís glamour in an artist dying

a heroic death?" "Rather the opposite. I think the artist should

live longer to record atrocities and beauty. But I am not about

to paint flowers, not now anyway. Still, you can neither practise

nor dream if fear is a constant factor in your life. In any case,

life is about that: everything, every action is political. It can

be documented and reviewed according to the viewerís taste." Though

he has created only three works which deal directly with the spectre

of Mugabe - The Presidential Wall Paper, The True Believer and The

End of Silence - the artist often finds discussing Zimbabweís bespectacled

kingpin harrowing. "I might sound brave, but I am very disturbed.

I am concerned about my family. I am torn apart... you see, my mother

still lives in Zimbabwe. I also love the country. I still want to

go back. Itís been three years since I last went back. The country

is in my bloodstream." The third time I meet Kudzi, our talk is

all about the identity he is creating and about living in a country

that is, like its President, torn between pro- and anti-Mugabe camps.

He is acutely aware of the battle lines - between those who passionately

feel that quiet diplomacy is a game for wild birds, and that Mugabe

should be pressured to step down; and those who are motivated by

a different set of racial and economic considerations.

"I have been

called a traitor several times. Once when I was doing an interview

on [Gauteng radio station] Kaya Fm, a caller remarked that I am

not patriotic about my country. "The underlying message is: ĎYou

are living large in this country, a liberated African country, getting

media attention, yet you are not grateful for the contribution Zimbabwe

has made. Sell-out!í If Zim was not wobbling by, soaking in pain,

I wouldíve dismissed the caller for being quite funny on a serious

talk show. Thereís pressure on commentators - artists are commentators

- to take sides. Thereís pressure, mostly from black South Africans,

to overlook the atrocities in Zimbabwe. For them, Mugabe is the

ultimate liberator." He shrugs, lights up a fag and sighs. "The

untouchable. Sad." "Do you smoke when you are frustrated?" I wonder

out loud. "Yes. Like now. This is a stressful discussion." As if

propelled by a similar force, we break beat and change the topic,

although it will resurface. It seems Kudzi is unable to shelve Uncle

Bob for good - until ... unless ...

Besides Uncle

Bob, Kudzi is also passionate about the commercial imperatives that

define what is and what is not mainstream. Heís also maddened by

the bling dictates of corporatised hip-hop that define "the hip-hop

generation". But, like his heroes, the late artistic genius Jean

Michel Basquiat and the invisible "graff" icon Banksy (both hip-hop

artists who succeeded in taking graffiti from the streets to the

high-street art galleries), Kudzi is trapped in a hot capsule -

a revolutionary who canít escape the lure of glamour the mainstream

art world inevitably holds for the radicals. "Primarily my art is

about communicating with the hip-hop generation. It might not be

expressing an entirely hip-hop aesthetic, but it sets out to talk

to my peers, and they are mostly in hip-hop, be they the music consumers,

poets or fashion crowd - the glue that binds us is hip-hop." As

with his Zimbabwean demons, hip-hop culture does not sit entirely

comfortably within the Kudzi philosophy. There is a sense that he

is the sort of adherent who has burst beyond the cultureís stasis

and yet, like Erykah Badu sang: "Hip-hop you are the love of my

life". The subtext reads: "F**cked up as you are, I will come pray

on your tombstone."

"Am I a hip-hop

artist? No. But I pencil in hip-hop culture, use it for what I seek

to achieve. Itís agitative and also a common language through which

youth, across the universe, communicate. It does not define me but

is part of my expression, especially the graffiti aspect." Back

at his Braamfontein studio, we venture into an area often dismissed

as hip-hop intellectual gymnastics. "Hip-hop? Yep! I can relate

to it. It samples varying bits and pieces of other musical styles,

references different personalities and recreates itself as it goes.

Its single identity is made of varying stories. You see, hip-hop

is very post-modernist, mah man." I see. But Kudzi is not the first

mind gymnast. Since the 1980s to this day, exponents such as Public

Enemy, Dondi, Lesego Rampolokeng and Mos Def have sought to elevate

hip-hop culture to the status of a political tool against the status

quo. "But it can bottle you in. A situation Iím uneasy about. All

my life, Iíve wanted to be free." For such a young man who uses

the profits from his work to fund his siblingsí tertiary education,

the idea of freedom remains just that: an ideal. "At least it is

an ideal worth fighting for. What should I do? Curl up and die?"

Doesnít it sound like Nelson Mandela circa the Rivonia Trial?

By the time

the interview ends it is too late for Kudzi to go back to Pretoria.

On the way to a friendís place in Melville, where he will crash

for the night, it emerges that all his friends are white. "So what?"

I think. But race will not be easily tucked away here. Asked if

thereís anybody who can give a critical appreciation of his work,

he offers as referees two white professors at Tukkies. Again, "So

what?" Another person in the car asks him about the gallery that

is hosting his exhibition. Kudzi says the gallery is in Melrose

Arch and is owned by Mike Obert. Oh, by the way, Obert is a young,

white American who has lived in Zimbabwe and who has major issues

with Mugabe.

Outside, early

winter bares its fangs. Inside the jalopy the mood yo-yos between

unease and relief. The driver puts in an Ali Farka Toure CD as a

calm-downer. If one were given to careless, racist conclusions it

would be easy to shrug Kudzi off as an example of "black talent

for a white tool". But sensing he will be crushed by this, I throw

in some banter: "Oh, but a man has to live. Whatís so bad about

being surrounded by a sea of helping hands, black or white?" It

doesnít help. People are people.

Kudzi prefers

a cut-to-the-chase approach: "Look," he sighs, "these people just

happen to be my friends. I never sat down to create a line of white

donors. Nobody pays me to do what I do. I donít care whether these

are the same people seen to be waging a battle against Mugabe. I

am doing my bit for my people. Do people realise how stressful that

is?" Kudziís comment reminds me that in the 1950s writers such as

Nat Nakasa in South Africa, and James Baldwin - the toast of the

Left Bank in Paris - were criticised for being "the beneficiaries

of European benevolence". Can no one do their thing without being

judged for the people they socialise with? Or do "those strutting

with the cats, waiting to pounce, have no right to call themselves

mice?" A sense of paranoia creeps up again. Kudzi pounces on it:

"Thatís the story of my life.I have to look over my shoulder all

the time. Wherever. Travelling on trains or walking the streets.

Painting or thinking of my family. I live in permanent fear." I

feel for him, but I am also familiar with the plight of thousands

of Zimbabweans forced to scrape by, doing the worst jobs imaginable.

By comparison, Kudzi looks like an intelligent fun-seeker, performing,

as he plods along, one helluva revolutionary trapeze act. Still,

Kudziís fear is not entirely unfounded. See, just because youíre

paranoid it doesnít mean theyíre not out to get you.

Please credit www.kubatana.net if you make use of material from this website.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License unless stated otherwise.

TOP

|